PREVIOUS | NEXT | HERITAGE TRAIL HOME

| The ice retreats. What are now Kelly’s Point and Tinderbox (over there across the Channel) are linked by a game-rich grassy plain. Can you see it? But the sea is rising at the rate of a metre a year, and 8000 years ago Bruny Island splits from mainland Tasmania, with the present sea level stabilising around 6000 years ago.

The island, now predominantly grassy woodland, has become home to eight hearth groups of Aborigines, 50-80 people all told. These are the Nuenonne, one of four tribes that comprise the South-East language group. The families traverse the island in search of food, hunting wallaby, seal, possum and other small animals. Plants, tubers and fungi are harvested, eggs are collected, shellfish are gathered. The islanders live in bark windbreaks or half-domed huts. Spears are a tool for hunting kangaroo, with waddies for killing seals. Sharpened stones are used for skinning. The few precious items required are carried in small baskets. Each year the Nuenonne cross the Channel to visit those with whom a special relationship exists, particularly the Port Davey people, who share common languages with the South-East tribes. The Nuenonne are, then, familiar with the pathways and game habits of a large part of Van Diemen’s Land. Nevertheless, in common with all the South-East tribes, their lives are closely tied to the food-rich coast. Historian Lyndall Ryan observes that they are ‘the most maritime of the Aboriginal Tasmanians’. Given the geography of European exploration and settlement in Van Diemen’s Land, it is inevitable that the Nuenonne are the first of the original peoples to have substantial contact with Europeans and to suffer atrocities as a consequence. Then, in 1829 George Augustus Robinson establishes the ‘friendly mission’ on Bruny Island. Within six months a respiratory contagion kills two-thirds of the island’s Aborigines. Small wonder that the Bruny people’s word for Europeans, as recorded by Robinson, translates as ‘devils’. Nevertheless, when Robinson finally takes his mission across the Channel, many Bruny Islanders accompany him, and their knowledge of the larger island is crucial to the ‘success’ of the mission. As Robinson concedes in a rare moment of humility, they enabled him ‘to traverse a huge tract in a very short time’.

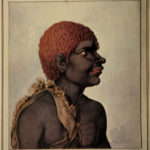

Further reading Duyker, E. (2003), Citizen Labillardiere, (Melbourne University Press, Carlton [Vic.]). Johnson, M., and McFarlane, I. (2015) Van Diemen’s Land: An Aboriginal History, UNSW Press, Sydney. Plomley, N.J.B. (1983), The Baudin Expedition and the Tasmanian Aborigines 1802, Blubber Head Press, Sandy Bay (Tas.). Robinson, G.A. (2008), Friendly Mission: The Tasmanian Journals and Reports of George Augustus Robinson 1829-1834, 2nd edn, NJB Plomley (ed.), Queen Victoria Museum and Art Gallery/Quintus Publishing, Launceston’; especially ‘Prelude’ and section ‘Bruny Island mission 1829’. Ryan, L. (1981), The Aboriginal Tasmanians, University of Queensland Press, St. Lucia (Qld.). Images The images of Ouriaga and the Aboriginal wind-break are from NJP Plomley, The Baudin Expedition and the Tasmanian Aborigines, 1892 (Blubber Head Press, Hobart, 1983). The sketch of an Aboriginal canoe by Peron is from the Museum of Quai Branly, Paris (ref 54_3339). The image of an Aboriginal basket is from Lesueur and Petit’s, Voyage of Discovery to the Southern Lands, An historical record; Atlas. (Artus Bertrand, Paris: 1824.). It was sourced from a facsimile edition published by The Friends of the State Library of South Australia, 2008. (Translations by Peter Hambly and Introduction by Sarah Thomas). |

ListenGallery(Click to enlarge images) |