PREVIOUS | NEXT | HERITAGE TRAIL HOME

| It is 22 January 1802, and the Geographe and the Naturaliste drop anchor in the Channel. Their very names tell us why they are here, cruising the southern seas.

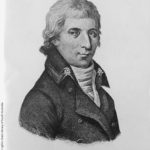

Imagine yourself a junior officer. This is an ill-starred voyage, one wracked with scurvy, malaria and dysentery. Things are worst on the Geographe, the 30-gun corvette of the expedition’s commander, Captain Nicolas Baudin. There is so much sickness there that it is often hard to muster enough fit hands to sail the ship. And then there’s the powder-keg politics. In France the monarchy is no more, swept away 12 years ago in the French Revolution. Napoleon rules. Baudin, though, is not reconciled with the Republic, unlike his liberally-inclined scientists. The naturalist, François Péron, passionate, articulate, and literally battle-scarred from service in the republican army, is a lightning rod for dissent. The expedition has been plagued by desertion and mutiny. It will be away from France for three long years. The scientists insist upon their petty luxuries while ordinary seamen die of starvation. Baudin deems them effete – and indeed, only seven of the 23 scientists will return to France. It is a deeply unhappy expedition and Baudin himself will die in Mauritius on the voyage home. And yet… these supposedly ‘soft’ scientists throw themselves into their work, with remarkable results. 2500 species of fauna are recorded and 100,000 specimens are collected. They assiduously preserve and describe, while the expedition’s two artists, Lesueur and Petit, each originally recruited as an ‘assistant gunner’, brilliantly draw. Many of the living specimens are destined for Empress Josephine’s garden at Malmaison. In Van Diemen’s Land, and especially here at Bruny’s northernmost extent, the scientists’ observations will be the most meticulously detailed of all pre-invasion descriptions of Aboriginal life. But you have just anchored in the Channel, and the 26 days you will spend here will be the happiest of the expedition’s entire three years. The scientists are drawn to Bruny’s northern extremity – right here – and Baudin himself leads specimen-collection parties onto the island. Inevitably contact is made with the Nuenonne, and this results in several remarkable interactions. The Aboriginal children, Baudin writes (on one instance), ‘were playing happily with our men… the men ran races with them, did somersaults, and played various other games’. On two occasions there are ‘incidents’, Baudin himself being grazed by a thrown stone. But these are minor and against the grain. Delight, trust and wonder characterise the meetings, and you are swept up in the heady amazement of it. Further reading and image sources Plomley, N.J.B. (1983), The Baudin Expedition and the Tasmanian Aborigines 1802, Blubber Head Press, Sandy Bay (Tas.). Anthony J Brown, Ill-starred Captains Flinders and Baudin, Crawford House Publishers, 2000. The images of Lesueur and the Geographe’s letterhead were sourced from this book, with the original images held in the Collection Lesueur, Museum d’Histoiree Naturelle, Le Havre. Jill, Duchess of Hamilton, Napoleon, the Empress and the Artist, The story of Napoleon, Josephine’s garden at Malmaison, Redoute and the Australian plants, Kangaroo Press, 1999. The images from the frontispiece of Lesueur and Petit’s Atlas, of Malmaison, and Redouté’s floral illustrations on this page and the corresponding panel are from this volume. The image of Baudin is from the State Library of South Australia’s portrait collection, ref: B+5793. The image of Péron is from Wiki Creative Commons. Useful entries on many of the French expeditioners can be found in the French Australian Dictionary of Biography, eg. Baudin, Petit, Lesueur, Freycinet. |

ListenGallery(Click to enlarge images) |